Welcome to One Thing Better. Each week, the editor in chief of Entrepreneur magazine (that’s me) shares one way to be happier and more effective at work — and build a career or company you love.

Today’s edition is sponsored by Upwork. Its new playbook can make your company more innovative. (More details at the end of the newsletter.)

Today’s one thing: Giving it your all.

That one thing, better: Giving it your best.

You’re working hard on something, but it isn’t working.

Maybe you hit a dead end on a project. Or fell behind on a deadline. Or you’re staring at a blank page, unable to create something brilliant.

Today, we’ll fix that problem. You’ll improve your performance. You’ll have a breakthrough idea. You’ll rock through your tasks.

All you need to do is this: Use less of your brain.

It’s a counterintuitive idea I stumbled upon myself, then discovered has deep roots in psychology.

I’ll explain how to do it — but first, I’ll show you how it helped me.

How I became a sharpshooter

Last year, I bought a basketball game and set it up in my basement. I said it was for my kids, but let’s be honest — it was for me.

I love this thing. It’s a great way to relax. And as I’ve played, I noticed an interesting pattern:

🏀 When I shoot in silence, I’m just so-so. My high score is maybe 50.

🏀🔥 When I play songs I love and sing along as I shoot, I become Steph Curry. My current high score is 121.

Why? I developed a theory: When I’m shooting in silence, I’m focuced on my shot. But when I’m listening to music, my brain is partially occupied and my body takes over — and that’s when I shoot better.

It’s like a formula — less brain, more instinct!

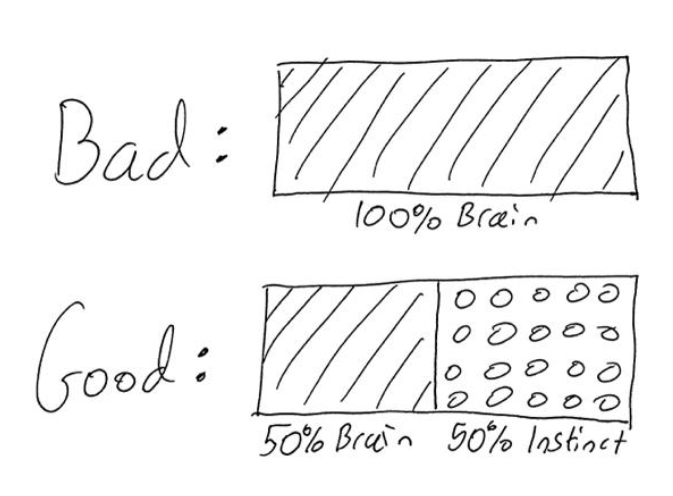

I sketched it out:

I wondered: Is this a thing? So I started researching, and oh yeah — it sure is a thing!

The perfect balance of effort

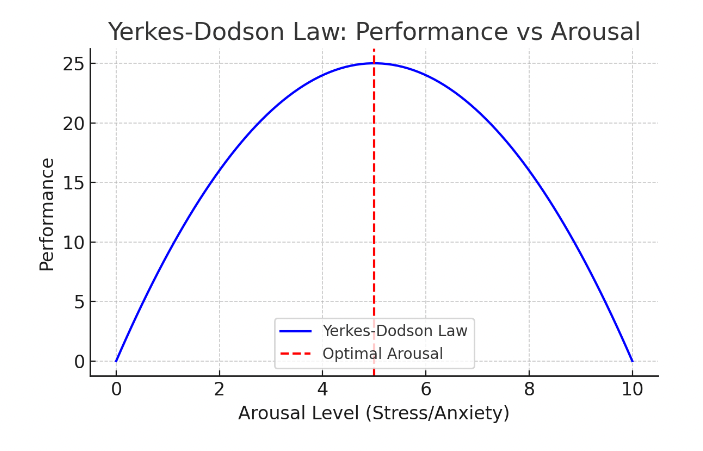

In 1908, two psychologists developed what’s called The Yerkes–Dodson Law. It’s basically the Goldilocks theory of performance — and it looks like this:

Here’s what this means: If you’re too passive or too intense about something, you’ll perform it poorly. But when you get that stress just right, your performance spikes.

In 1990, psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi gave us a more casual way to describe this phenomenon: He called it flow — and he said that people are most creative, productive, and happy when they’ve achieved it.

He described flow as…

“a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.”

In other words: When you do something without thinking too hard about doing it, you do it better. Just like me shooting baskets in my basement.

That got my wondering: Can we apply this elsewhere? How else can we subtract our brains, and increase our instincts?

Let’s start here:

When to dial back your brain

I’ve found three instances that work for me:

1. Walking and talking.

My day, like yours, is full of video calls. I don’t like this. It’s too much focus.

So I’ve started an experiment: Whenever it feels appropriate, I suggest that we go off video. “I’m going to take a walk while we talk,” I’ll say. “I’ve been stuck in front of the computer too long.”

At first, I worried that this would seem unprofessional. But people thank me. They don’t want to be on video either! And some have even joined me in walking.

When I walk, my brain is engaged by multiple things — and instinct can take over. Ideas flow more freely. I become more animated. The meetings are better.

I strongly suggest this. Or even better, invite people to take an actual IRL walk with you! Multiple business partnership of mine started this way.

2. Ideas on the fly.

People often ask me: Where do I get the ideas for this newsletter?

Here’s the answer: I do not get them by thinking of ideas for the newsletter.

Instead, my system is simple: Whenever I stumble upon an interesting idea — based on something I said in conversation, or heard from someone else, or just experienced in passing — I’ve trained myself to think: That could be a newsletter!

Then I write it down in my Reminders app. For example, here’s what I wrote a few weeks ago, which prompted the newsletter you’re reading now:

Then I start writing — and when I write, I just write. I see where the words take me, even if it means abandoning some of my original concepts. (As you’ll see, some of the stuff in my note never made it into this newsletter.)

It’s all part of a belief of mine: The best ideas are generated on the fly.

This goes for collaborations too. When I’m in meetings, I’ll often say: “I’m just going to think aloud here …” and then I’ll work an idea out in monologue or conversation.

3. Don’t micromanage the moment.

I give a lot of keynote talks. I’ve never written down or memorized one.

That’s not to say I wing it! I create an outline, rehearse, and refine. But I also structure my talks around familiar stories I love telling, and exercises that I’ve shared many times. That way, I intuitively know this stuff — so when I’m on stage, I’m acting on instinct. I sound fresh, and I can react to the audience in real time.

If you memorize something word-for-word, the opposite will happen: You’re anchored to your words. You’ll be stiff. And if you lose your place, you’ll never find it again.

I take a similar approach to interviews. I’ve interviewed A-listers like The Rock, Jimmy Fallon, and Michelle Pfeiffer, and I NEVER write out a list of questions — because if I did, I’d be stuck thinking about the next question instead of listening and responding. So here’s how I prep: I learn a lot about them, hypothesize a few directions the conversation could go in, and then let it flow.

The possibilities are endless!

As you read the examples above, you might have thought: “That won’t work for me.” All good! What works for me might not work for you. We have different instincts.

The point here isn’t to be prescriptive. It’s to focus less and feel more.

You’re at your best when you’re you, not when you’re trying to be you. So let go a little. Trust yourself. You’ve got this. Sing as you shoot.

That’s how to do one thing better.

One number shows why many companies will fail next year:

Yes, the scary number is 26.

Here’s where it comes from.

Upwork surveyed 1,500 companies, and asked what their top priority is for 2025. Most said they’re maintaining current operations, finding efficiencies, or other forms of staying the course — and only 26% said they’re focused on innovation, creativity and risk-taking.

It’s understandable — in uncertain times, our instinct is to bunker down. But look to history: During the ’08/’09 recession, the companies that kept innovating came out ahead of those that hunkered down.

Why? Because when disruption is over, innovators are fully modernized — while the others are behind the times.

So ask yourself: “When times are tough, how do I reinvent instead of retreat?”

Not sure where to start? Check out Upwork’s Work Innovators Report, which offers a playbook to keep your company innovative.

*sponsored