Welcome to One Thing Better. Each week, the editor in chief of Entrepreneur magazine (that’s me) shares one way to feel more successful and satisfied — and build a career or company you love.

If this email is useful to you, please share it with others!

Today’s one thing: Trying to get over it.

That one thing, better: Seeing it for what it is.

You want to be great all the time. But you’re not.

Some days you aren’t as smart, funny, or exceptional as you’d like to be. Your ideas seemed mediocre. Your efforts were a little meh. You know it’s not a big deal, but you beat yourself up over it anyway.

A few weeks ago, I had one of these days. I wrote about how I bombed on stage. Many of you sent me wonderful responses (thank you!), and shared your own struggles with imperfection.

I loved this admission from an amateur DJ. They wrote:

Whenever I fail to make the perfect set, or the perfect transition, I have trouble sleeping that night or I beat myself up for hours — even though everyone in the audience enjoyed the party without noticing my mistake.

I’ve been there. We all have. It’s frustrating: We didn’t fail, per se. There was no disaster. But we didn’t live up to our high standards and now we can’t let it go.

Today’s newsletter is for people like that.

I have two mental tricks to help you move on: I call them Thinking Downward, and the Grading Curve. They’ve helped me bounce back from my imperfect moments — and I think they can help you too.

Tactic #1: Thinking downward

Let’s say you’re that DJ. You fail to do things perfectly. Then you go home and obsess over it, imagining all the better decisions you could have made.

You’re doing something called counterfactual thinking. In other words, you’re creating alternate realities in your head, and then wishing those alternate realities were true.

I wanted to know: How do you snap yourself out of that? So I called an expert who studies this stuff — a social psychologist at Wake Forest named John Petrocelli. Here was his advice:

“This is going to sound a little funny, but the trick is to consider additional alternatives — to consider other counterfactuals.”

Because here’s the thing: There are actually two kinds of counterfactuals. The first is called upward counterfactuals, when we imagine how things could have been better. That’s our usual mode.

But there are also downward counterfactuals. That’s when we imagine how things could have gone worse.

Here’s an amazing study, which shows the impact of these two modes of thinking:

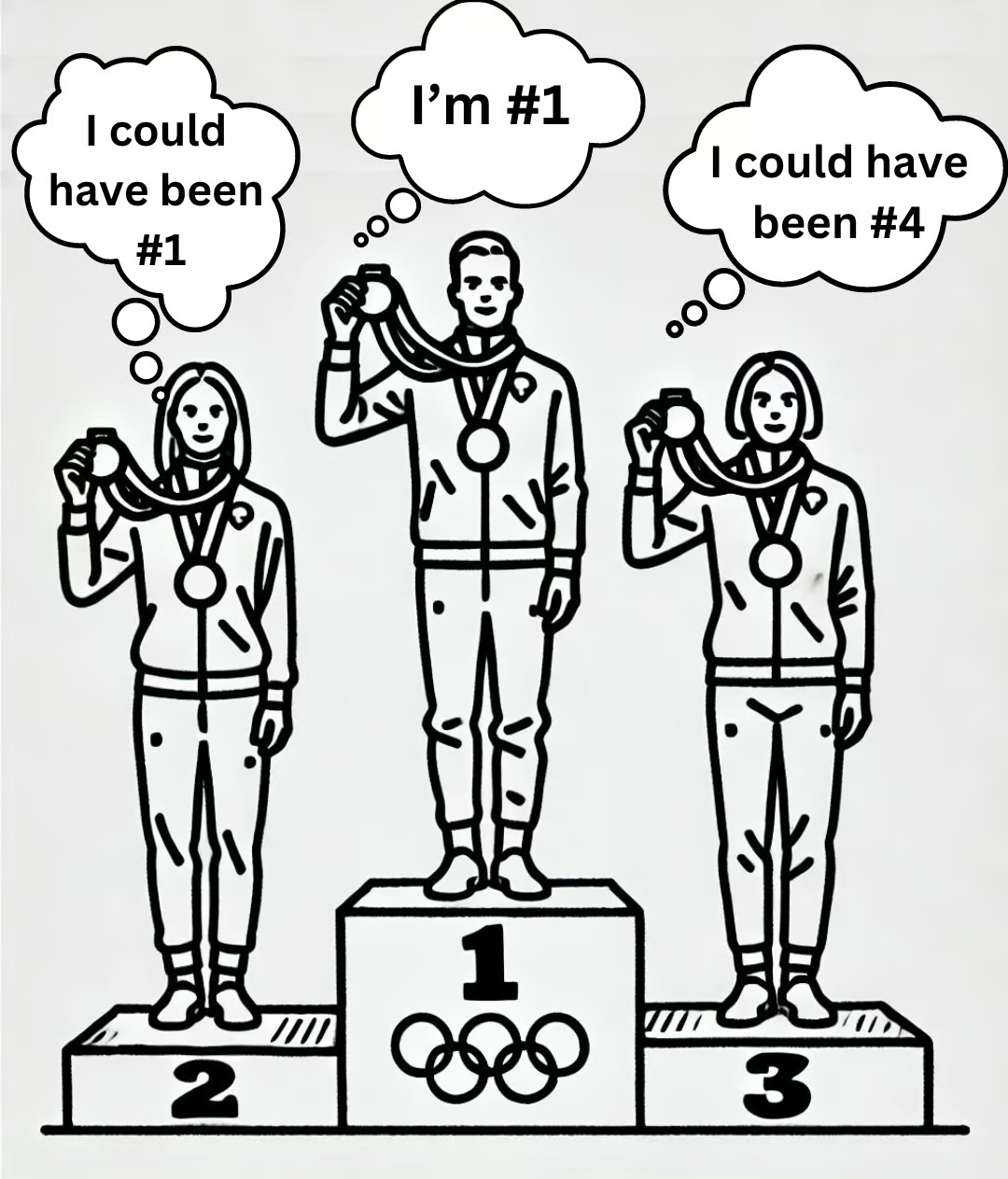

Scientists have studied Olympic medalists, to see how happy or upset they are when receiving their medals. The answer: Silver medalists are the least happy.

Why? Because the dynamic looks like this:

In other words: The silver medalist is thinking upward, about how they could have gotten gold. The bronze medalist is thinking downward, about how they might not have medaled at all. One feels deficient. The other feels fortunate.

That’s why John Petrocelli gives his advice: We can’t easily turn off counterfactual thinking, so you might as well fight it with more counterfactual thinking. If you’re stuck imagining all the ways things could have gone better, start imagining the ways it could have gone worse. Because that was an option too. You could have flopped.

Now here’s my second mental trick…

Tactic #2: The grading curve

Whenever you do something, you’re really experiencing two things at once: You know what you aspire to do, and then you see what you actually do.

Unfortunately, we don’t always do what you aspire to do. That’s what kills us.

So remember this: Your audience didn’t see both those things. Your aspirations are invisible to them. All they saw is what you actually did — which means they’re not comparing it against anything.

They don’t know the joke you forgot to tell, or that great point you didn’t make. They don’t know the perfect transition you missed in that DJ set. Hell, they might not even know what a perfect transition is.

Remember the “grading curve” from school, when teachers would bump student scores up? That’s kinda what’s happening here, and it looks like this:

Your B+ is someone else’s A+.

Your B is someone else’s A.

Your C is someone else’s B.

When you’re feeling down, it’s helpful to see things through other people’s eyes. Pause to ask yourself: “What did other people actually see or hear?”

List it out, if you must.

For example, I recently went on a morning TV show and delivered a meh performance. On my way home, I kept obsessing over the missed opportunities. My delivery could have been sharper. My on-air banter could have been funnier. And did I ramble on that second question?

I texted the show’s host, asking if I did OK. Her reply was kind: “You’re better than you think you are,” she said.

That helped me step back and imagine what people actually saw. I made a list in my head.

- They saw a guy being friendly and warm

- They saw a guy who made some good points

- They saw a guy who looked calm and confident

Meanwhile, here’s what they did notsee…

- They did not see the things I meant to say, but didn’t

- They did not see the other way I could have answered that question

- They did not see a guy nervously obsessing on the way home

Was it the best TV segment they’ve ever seen? No, but nobody expected that. And nobody was promised that! My definition of success was too big for the moment.

It’s time to be OK with being OK

We have amazing days. We have terrible days. But most of our days are somewhere in the middle. They’re just fine. We passed the test. We did the thing. We made it.

Let’s give ourselves credit for that. The middle is its own kind of success.

The middle means we didn’t destroy everything. The middle means we showed up and learned. The middle means we get another shot tomorrow. And don’t forget — other people might not even think we were in the middle! They might think we were great! Or more likely, they might not be thinking about us at all.

Imagine that DJ at the turntables. Now look 20 feet away. Find a couple dancing to the music. They’re having a great time. They’re going to go home tonight and feel good, and they’re going to think that DJ did an A+ job, and they’ll never know or care what that DJ didn’t do, because all they care about is what the DJ did do.

Greatness is more achievable than you think.

That’s how to do one thing better.