Welcome to One Thing Better. Each week, the editor in chief of Entrepreneur magazine (that’s me) shares one way to level up — and build a career or company you love.

I was traveling last week, so today I’m sharing one of my favorite posts from last year…

Today’s one thing: Talking to someone, but feeling unsure.

That one thing, better: Swim to shore.

You’re in the hot seat!

Maybe you’re giving a presentation. Or are being interviewed for a job. Or you’re a guest on a podcast. Or you’re just talking with someone intimidating.

In many ways, at many times, you’ve surely felt this same flash of panic: Someone has asked something of you, or they’re expecting something of you, and you think…

I do not know what I’m talking about right now.

Today, I’m going to give you a way to sound and speak with more confidence. I’ve been using this trick for years, and it has helped me avoid countless public embarrassments.

I call it swim to shore.

Here’s a classic danger moment

After I give a keynote talk, I usually take questions from the crowd. Sometimes, someone asks me a totally unfamiliar question and I think: Crap, I don’t have an answer to this.

Then all eyes are on me. I need to say something. And it needs to happen now.

The first few times this happened, I tried to answer their question very directly. Often I’d stumble. Or sound hesitant. I always regretted it afterward.

Then I started to break the situation down. What was actually happening in that moment?

I realized I was making two distinct mistakes:

Mistake #1: I prioritized their question over what really mattered.

Mistake #2: I answered on their terms, not mine.

Let’s look closer at each mistake.

1. What really matters?

Sometimes, the expectations for you are very narrow.

Maybe you’re meeting with an investor, and they want to know your customer acquisition cost. Maybe you’re giving a presentation to your boss, who wants to understand a project in detail.

In those cases, you better be prepared.

New to this newsletter? Subscribe!

But most of the time, expectations are not that narrow. On stage, on a podcast, in a job interview, in conversation — in these cases, the expectations for you are broad.

Which is to say: People don’t expect you to say a specific thing. They just expect you to say satisfying things.

When someone asks you a question, they’re really just prompting you to speak more. It’s as if they’re saying: “Here’s a general topic — can you speak some words about it?”

When you think of it this way, you realize that people’s questions aren’t the most important part of the exchange. Your answer is the more important part. That’s where all their expectations lie. Your audience — whether it’s one person or thousands — just wants you to say good stuff.

And how do you do that? Well, let’s look at mistake #2:

2. Whose terms do you answer on?

Someone asks you a question and you don’t know the answer.

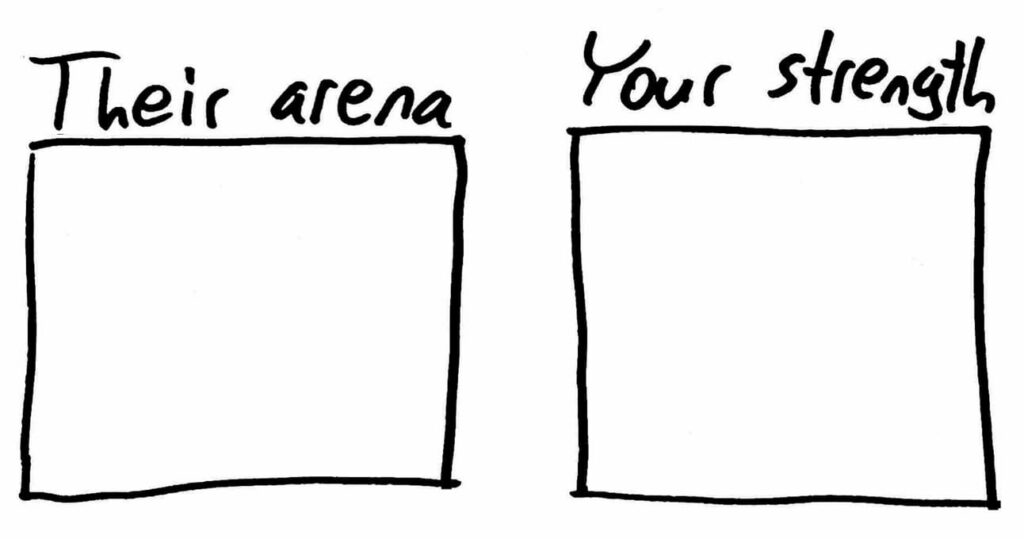

Let’s draw a chart of what this looks like. It’s two separate spheres — there’s the arena they’re coming from, and there’s your strength. It’s like this:

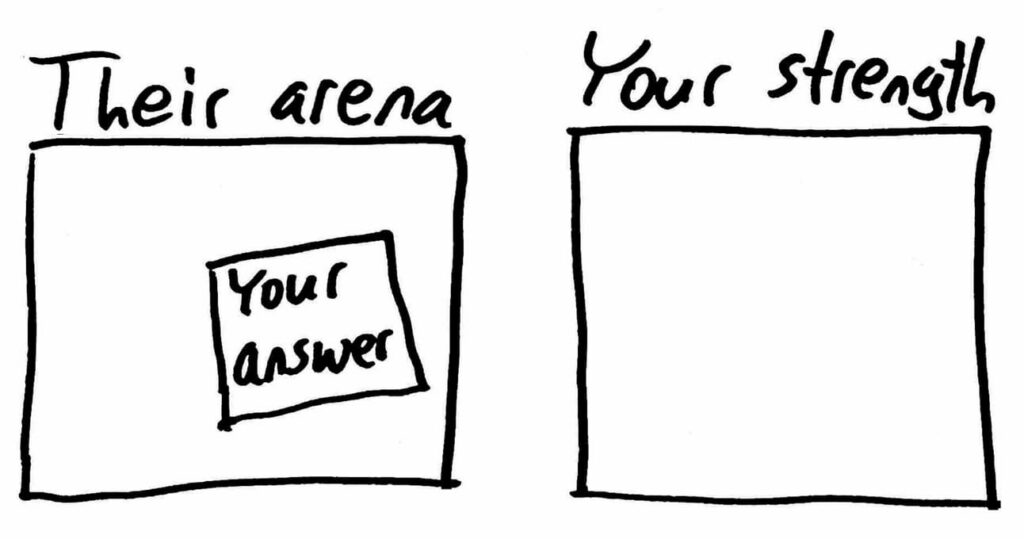

When we’re asked a question, our instinct is often to answer it directly and literally — even if we don’t have a good answer. That’s what I tried to do in my Q&A sessions, when someone stumped me with a question.

So, what does that look like in our chart? It’s like this — your answer contained inside their arena, and very far away from your strength.

But this is a mistake! Why? Because like I said above — most of the time, nobody cares about your answer to their hyper-specific question. They just care that you say something valuable. And if you can’t be valuable in their arena, then you’re not being valuable at all.

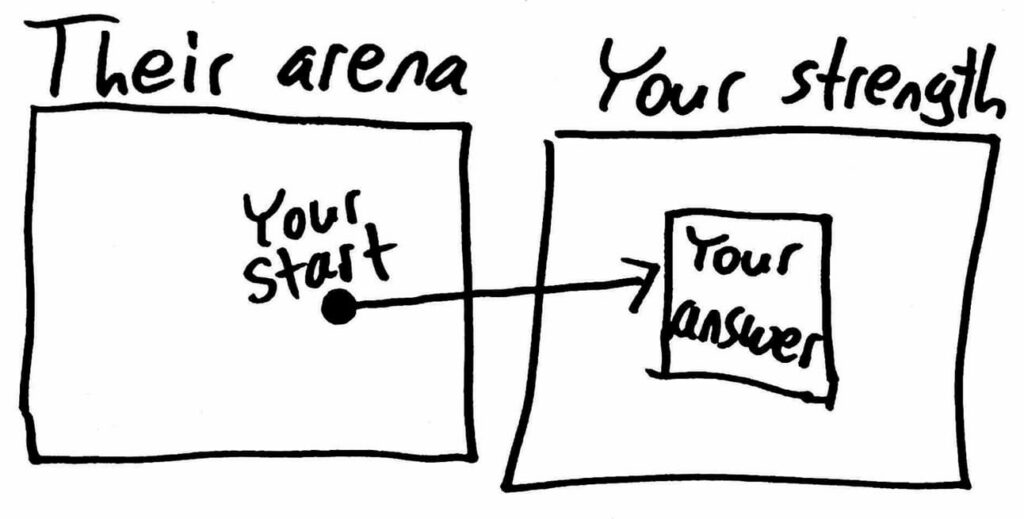

You need to get the hell out of there — and move towards your strength.

To do this, you start with the premise of their question. You acknowledge it, appreciate it, and engage with it. But you head towards your strength (which is what we’ll get to next).

It looks like this:

In my head, I’ve started to think of this as swim to shore.

It’s a visual metaphor:

Imagine it: Every time someone asks you a question, it’s like they’ve picked you up off the ground (your strength!) and they tossed you out into the water (their arena!).

You can only tread water for so long. If you try to stay out there too long, you’ll drown. So you you swim to shore — which means swimming through their question, but answering it on dry land.

And what exactly is on that land? Well, it’s time to ask:

What is your strength?

Think about this for a moment. When you’re speaking — to an individual, or to a group — what are you most comfortable talking about?

Maybe it’s a specific body of knowledge. Maybe it’s a mode of engagement — that you’re best when being thoughtful, or funny, or philosophical, or personal. Maybe it’s a mode of communication; perhaps you’re amazing at asking questions or breaking things down in tactical ways.

Whatever it is, that’s your strength. That’s where you need to swim to.

Me? My strength is storytelling. I know how to tell a tale in a compelling way, and then draw a lesson out from it. And I have a ton of them.

So let’s say I’m on stage. I just gave a keynote and it’s Q&A time. Someone raises their hand and asks, “How can a senior VP of a Fortune 500 company lead their team through economic uncertainty?”

Years ago, I would have heard that question and panicked.

Why? Because there are specialists and consultants and executives who could answer this question easily — and I am not them. This isn’t my specific area of expertise. And that made me feel like a fraud.

But today, I don’t panic. Instead, I think: swim to shore.

Like I said — for me, storytelling is shore. So I think: This person is asking about leaders navigating change. What stories do I have about leaders doing that?

Then I remember one. It’s not about a senior VP at a Fortune 500 company, but who cares? It’s a good story! And it has a good lesson about empathy and communication.

So I begin: “Thanks for that question, and it’s an important one — because in times like these, teams will be looking for strong leadership from people like you. And it reminds me of a leader I spoke with a while ago…”

Then I tell that story. It captivates the audience, because I am leaning on my strength. Then I share the lesson of that story, and bring it back to the questioner. I might say: “So look, I’m sure that some Harvard Business School professor could give you a detailed lecture on the 20 things to do right now. But in my experience, the starting point has to be that lesson I just shared about empathy and communication. Because without that, nothing else will follow.”

See what I did? I didn’t dodge the question, but I also didn’t get trapped by it. Instead, I gave my answer based on my strengths, and I did it with confidence because I swam to shore.

You don’t need to know everything. You just need to know what you know.

That way, you always know what you’re talking about.

That’s how to do one thing better.