Welcome to One Thing Better. Each week, the editor in chief of Entrepreneur magazine (that’s me) shares one way to achieve a breakthrough at work — and build a career or company you love.

Today’s edition is sponsored by NeighborShare — the easy-to-use platform where you can help real neighbors in need. Read more below.

You messed up. Or something went wrong.

Your first instinct is to hide. Or act like it didn’t happen. Or feel a wave of shame.

But wait!

You should know this: According to research, your mistakes make you more likable — so long as you present them properly.

Today, I’ll show you what to do, why it works, and how to use errors to your advantage.

But first, let’s start with a simple, funny, charmingly effective example:

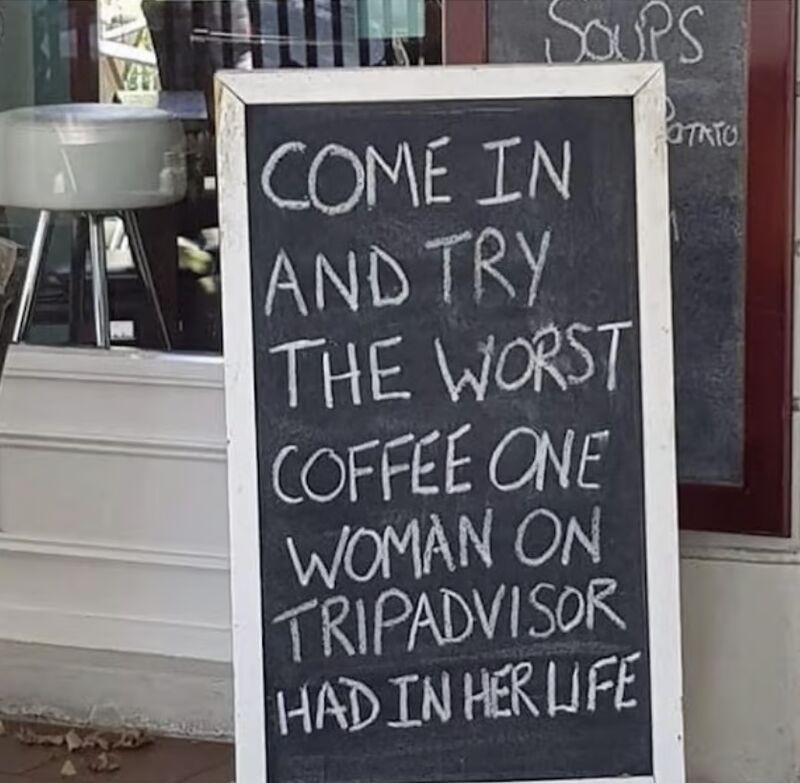

Would you buy coffee from these people?

This is my all-time favorite sandwich board:

This image has gone viral for years — and every time I see it, I want to try their coffee.

I was thinking about this sign recently, and it reminded me of a charming Idina Menzel video. Did you see this one?

She’s on stage, repeatedly fails to hit a high note, and the crowd adores her for it.

It got me wondering: Why? Like, why do our brains find errors so appealing and charming? Is there a reason for it, and better yet, a way to control for it?

After some research, I found an answer: This is a known psychological phenomenon called the Pratfall Effect — and it just might be the most liberating science you’ve ever heard.

The science of lovable mistakes

Here’s the origin story. In 1966, a psychologist named Elliot Aronson published an interesting experiment:

He gathered a group of college students and split them into four groups. Each group listened to a recording of someone taking a quiz, but with some key differences.

Here’s what each group heard:

- The person did okay on the quiz.

- The person did okay on the quiz, then spilled coffee on themselves.

- The person aced the quiz.

- The person aced the quiz, then spilled coffee on themselves.

Afterward, participants rated how likable the quiz-taker was. Here were the results:

- The most likable person was the one who aced the quiz and spilled coffee.

- The least likable person was the one who did okay on the quiz and spilled coffee.

- Those who didn’t spill coffee, whether they aced the quiz or not, were rated about the same.

In short, we learned this: Mistakes can make someone either more or less likable, based on how competent they already appear.

In 1966, Aronson called this The Pratfall Effect.

Why does this work?

If you ace a quiz and then spill coffee, you’re lovable — but if you fail that quiz and then spill coffee, you’re just a hot mess. Over the years, researchers have found many nuances to this. The effect can change based on someone’s self-esteem, the context of the mistake, and more. But the general pattern holds.

So… why?

Here’s the thinking: People admire perfection, but they don’t relate to perfect people. Perfection makes someone seem intimidating and inauthentic.

Mistakes, on the other, make people more relatable and human. Their vulnerability triggers our empathy. And when someone slips up, we feel like they’re not hiding anything — which builds trust.

For example: That Idina Menzel clip was posted by a fan of hers, who wrote, “I love going to see real and genuine people on the stage and this was one of my fav moments of the night.”

This fan wasn’t there to see Idina be perfect. She was there to see Idina be a real person — and flaws enabled that to happen.

How to use your flaws

There are endless applications of The Pratfall Effect, but here are a few that come to mind first:

1. Marketing.

Make a mistake? Something go wrong? Ask yourself: Can I use this without undercutting my competency?

That coffee shop’s sandwich board was perfect: By acknowledging “the worst coffee one woman on TripAdvisor had in her life,” it displayed confidence and competence — almost daring you to try their coffee.

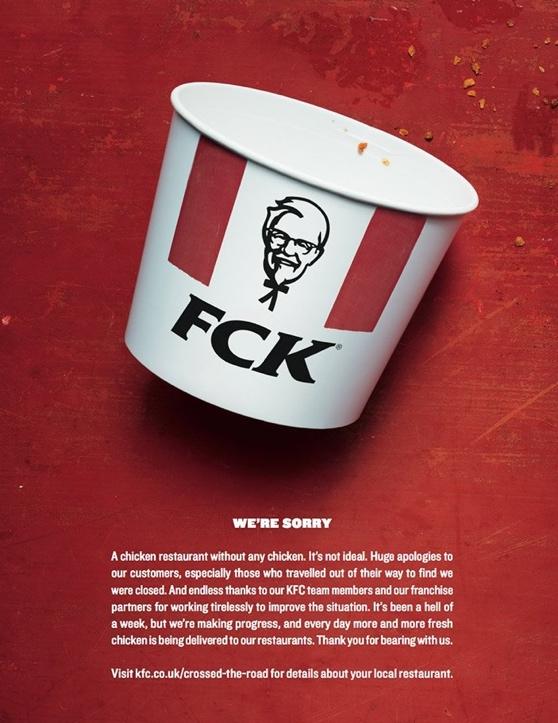

I’m also reminded of this brilliant apology from KFC, which it published after running out of chicken in the UK:

The bucket said FCK, which is hilarious, but the text was very earnest: The first words were “we’re sorry”, and KFC pledged to make it right. The ad was well received — because for customers who love KFC, this humanized the company.

2. Leadership.

No leader is perfect, which is why overconfident leaders are insufferable.

So long as your team trusts you, they’ll appreciate when you acknowledge your own mistakes. It shows that you accept responsibility, that you’re open to learning and growing alongside them, and that you won’t hold them to impossible and unfair standards.

3. Writing and speaking.

I share my mistakes in this newsletter all the time — like, for example, when I wrote about a keynote talk that went horribly wrong. Those editions always drive the most engagement, as people thank me for my vulnerability.

I do the same thing on stage in my keynotes. Many of my talk segments are built around a mistake I made, and then what I learned as a result. Again, people thank me afterward for being vulnerable.

I don’t mean to sound calculated, but to me, none of this is being vulnerable. I know that my audience will like these things! That’s because I’m following a very Pratfall Effect-like formula for sharing my errors:

- I display or explain that I am good at something.

- I describe what went wrong.

- I immediately pivot into what I learned, that helped me become better.

When I give a talk, for example, I never open by describing a failure. Instead, I spend some time displaying my competence — and only then get into a failure story.

This way, I’m using mistakes to humanize my skills, rather than to define myself as a failure.

Now here’s the best part

To be clear, I’m not saying that you share every error. That could come off as performative — or worse, like you’re just incompetent.

Instead, I’m saying this: Now you have a choice. You have a way to evaluate which mistakes to share, and how best to share them.

When something goes wrong, you can ask yourself:

- Does my audience already view me as competent?

- If so, does this mistake make me more likable?

And if the answer to both questions is yes, then that mistake wasn’t bad at all. It was the thing that makes you even more competent, and more likable, and more awesome than you already are.

That’s how to do one thing better.

Put A Little Good Back Into The World

Here’s an incredible organization run by a One Thing Better reader. Read on — and help your neighbors!

Thousands of families are one unexpected expense away from crisis. A car repair, an overdue bill, or an urgent medical cost can mean the difference between stability and hardship. That’s where NeighborShare comes in. Through our easy-to-use platform, companies, foundations, and everyday people can help real neighbors in need.

Unlike traditional crowdfunding, every need is vetted by trusted nonprofits on the ground — case managers and social workers at shelters, youth programs, domestic violence support organizations, and more.

- Are you a company leader? Businesses big and small partner with NeighborShare to engage their employees and customers in giving back to real people in the communities they care about. And the impact? It speaks for itself.

- Are you an individual looking for a more direct and transparent giving experience? (We were too! That’s why we created NeighborShare.) Find a neighbor to support today.

Whether you’re looking to integrate social impact into your business, rally your team, or just put a little good back into the world, NeighborShare makes it simple, transparent, and effective. Get in touch with us today.

*sponsored